Price Wars: David and Goliaths

The UK Newspaper Wars and the Nigerian Food Delivery Wars

Sometimes, startups act like we have nothing to learn from business history. And every once in a while, gravity reminds us that we do.

My master’s thesis was on the impact of price wars on markets.

A price war is not a promotion campaign gone slightly too far. It is a breakdown in the rules of the game. I have watched them play out across industries and across countries. Each one, unsurprisingly, resolved into one of five patterns.

Mutual destruction: Incumbents crater margins, then quietly pay for it by cutting the other things customers notice, reliability, quality, and support. Customers feel cheated, and substitution becomes easy. Everyone bleeds, and the category becomes cheap.

War-chest victory: The richest player “wins” the war of attrition, but inherits a broken category. There is a reset of anchor prices, and customers expect low prices. You win the war, then inherit the ruins. If meaningful competition remains, you risk becoming a cheap brand. If you truly lock in demand, you can later recoup through pricing power.

Refusal advantage: The player who refuses the subsidy war can use the chaos to reposition around dependable value. While others burn cash to buy volume, they build a reputation, consistency, trust, and premium perception. They do not just survive, they become the obvious alternative when the market sobers up.

Truce (tacit coordination): The war ends because everyone gets tired. Prices drift back up through discipline or capacity constraints.

Rule change: The war ends because the rules change. Regulation, platform governance, or market structure shifts that make subsidies unsustainable.

We’ll look at two examples.

The UK Newspaper Price Wars

Act I: The Caste System

Before 1993, the British newspaper market was not just an industry. It was a social hierarchy with price tags.

At the top sat the “Quality” broadsheets: The Times, The Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, and The Independent. Serious, expensive, and purchased by the establishment. They competed on prestige, not price.

In the awkward middle sat the Daily Mail. It was too serious for the tabloid crowd, too brash for the elite.

At the bottom sat the “Red Tops,” The Sun, and The Mirror. Cheap, loud, and built for volume.

Act II: The Race to the Bottom

Murdoch’s Times was struggling. It had prestige but was losing the circulation race. So he chose the nuclear option. He severed the link between cost and value.

The Times dropped its price from 45p to 30p on the 6th of September 1993. The Daily Telegraph, the market leader, matched the prices on 23 June 1994. The Times retaliated with a further cut to 20p (weekdays) a day later. Competition shifted from journalism to endurance. The Independent did not have a war chest. It tried to hold the high ground, even raising its price. It entered a long decline that eventually ended in a sale for £1 sixteen years later.

Act III: The Mid-Market Miracle

Under Paul Dacre, the Mail executed a strategy of disciplined aggression. It did not cut prices to follow the broadsheets into the trenches. It did not cheapen the product. And because it was not funding a loss-making ego contest, it invested in better coverage and better print.

Then the inversion happened.

The tier 1 broadsheets, trapped on razor-thin margins, started cutting costs. They thinned out foreign coverage, printed smaller magazines, and started covering sensational angles. Meanwhile, the Daily Mail began to look and feel like the premium product. Confident. Thick. Glossy. Culturally fluent. Not elite, but dominant.

The Outcome: A New King

By the time fatigue set in and prices began to climb again, the landscape had been permanently terraformed. The top tier had eroded its own prestige just in time for the internet to arrive and complete the devaluation.

Murdoch won the battle to keep The Times alive, but he turned that top tier into a cheap category, clearing the path for the Daily Mail to inherit the premium tier.

The Mail captured the aspirational class that the broadsheets abandoned in their race to the bottom. It became more than a newspaper. It became a political force that prime ministers learned to fear.

That is what price wars do. They do not just change prices. They change the hierarchy of power.

B. The Nigerian Food Delivery Price Wars, David versus Three Goliaths

Act I - The Caste System

Jumia Food entered early, in 2013, with the halo of Africa’s first unicorn. But first-mover advantage is not protection. It is simply an earlier start to learning hard lessons.

By 2020, the pandemic shifted consumer behavior, and food delivery moved from novelty to routine for many urban customers.

In mid-September 2021, Glovo launched in Nigeria, backed by Delivery Hero’s balance sheet. It came prepared, expanded into groceries and quick commerce.

A few weeks later, in October 2021, Bolt Food entered, drawing on the resources and operational muscle of a global ride-hailing company. These were the three giants.

That same month, Chowdeck was founded in Lagos. It did not have the pockets for a war.

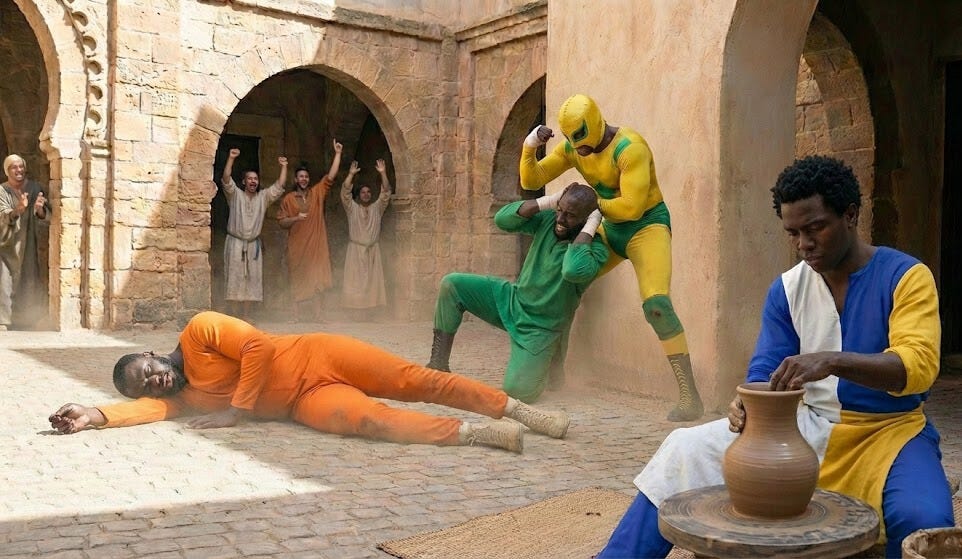

There were three big boys and one small kid who did not stand a chance.

Then Nigeria’s macroeconomic reality turned hostile. Between 2020 and 2023, the economy absorbed shocks that punished any model built on permanent discounting.

GDP contracted in 2020 after COVID and the oil crash. Inflation climbed. The naira weakened. Food inflation surged above 20 percent.

By 2022, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine spiked wheat and energy prices globally. Inflation rose further and food inflation worsened.

Act II: Quality Decay

2023 was the year of reckoning.

In Q1 2023, I was away on a business trip, enjoying the subsidies from the food delivery price wars. After a long day, I ordered jollof rice and chicken from Chicken Republic through Jumia Food. The delivery time promised was 45 minutes. It arrived almost three hours later.

The rider showed up as a passenger on a commercial tricycle. No insulated carrier. He had a regular school backpack. He barely spoke English. I paid and went upstairs to my room. And when I opened the pack, the chicken had clearly been half-eaten. Teeth marks, unmistakable. We both know it was not eaten by a staff member of Chicken Republic.

I took pictures, recorded a video, escalated to customer service, and asked for a refund. No one responded.

We were in the quality decline phase of the price war.

Two weeks later, back in Lagos, I signed up on Chowdeck.

Act III: Tinubu Shock-nomics

The decay had already started. Tinubu’s reforms simply removed the last cushion and forced every player’s hand.

On May 29, 2023, President Bola Tinubu announced the end of petrol subsidies. Fuel prices jumped, transport costs surged, and delivery economics tightened overnight.

In June 2023, the Central Bank unified exchange rates, and the naira weakened sharply. Every imported input cost more, and every operational inefficiency hurt more.

By August 2023, Chicken Republic announced a partnership with Glovo and ended its partnerships with Jumia Food and Bolt Food. The signal was clear. The market was tilting toward reliability and reach, not endless promotions.

By December 2023, two giants fell close together. Bolt Food shut down in Nigeria. Jumia Food announced it would exit multiple African markets, including Nigeria, by year’s end.

Jumia’s CEO described the market as driven by deep-pocketed, aggressive discounting, which is often a signal that the fight was not winnable on those terms.

Act IV: King David

The irony is sharp.

Bolt retreated from Nigeria but remained in Ghana. Jumia, the pioneer, walked away from food delivery. Glovo, which exited Ghana later, chose to stay in Nigeria. And in the background, Chowdeck survived and kept building. It had focused on unit economics. It paid riders well. It delivered what it promised.

By April 2024, Chowdeck raised $2.5 million in seed funding. In May 2025, Chowdeck expanded into Ghana. And by August 2025, it raised a $9 million Series A.

Jumia was early, but early did not save it. Bolt was global and well-funded, but Nigeria punished permanent subsidy models. Glovo exited Ghana but stayed in Nigeria. Chowdeck refused the subsidy war, then won anyway.

Just like the UK newspaper price wars. The fighter with the greater willingness to burn money won the price war. But they won a degraded market and a cheap brand. The deeper winner was the one who refused the wrong fight.

Chowdeck, like the Daily Mail, won because David does not beat Goliath by fighting on Goliath’s terms.

History rhymes most times.

But every now and then, it repeats in uncanny ways.