In strategy, most traditions are supply-side. They focus on what you must own, build, or control, resources, capabilities, and the industry structure you compete within.

Demand-side strategy flips the lens. It starts with the buyer. The job they are trying to get done, the frictions that lead to nonconsumption, and the price they are willing to pay to make progress.

The Chowdeck story cannot be explained by the usual supply-side stories we tell. We will have to understand it from the demand side.

Demand finds the beachhead. Supply builds the fortress.

Scene 1: Understanding the Food Delivery Market

In one of my earlier essays, I argued that to understand a thing, you had to look at it from multiple perspectives. The market has four moving parts: restaurants, food types, riders, and customers. Platforms sit in the middle, but the real product is coordination in a very volatile environment.

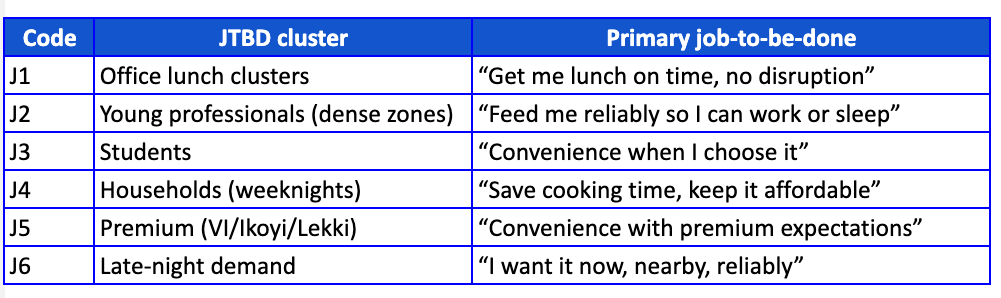

Lens 1: Demand clusters, who is ordering, and what job they are hiring delivery for

Demand in Lagos is not one market. It is pockets with different jobs-to-be-done, different urgency, and different substitutes when you fail.

Table 1: Customer’s Job-To-Be-Done

The student versus young professional split matters. Students can walk into a café, buy a snack, or wait it out. They have more immediate substitutes. Young professionals often cannot. When delivery fails, they improvise with Indomie, bread, or skipping the meal, and that pain makes them care about reliability differently. This is why a platform can dominate one occasion and collapse in another. A lunch promise is not a late-night promise.

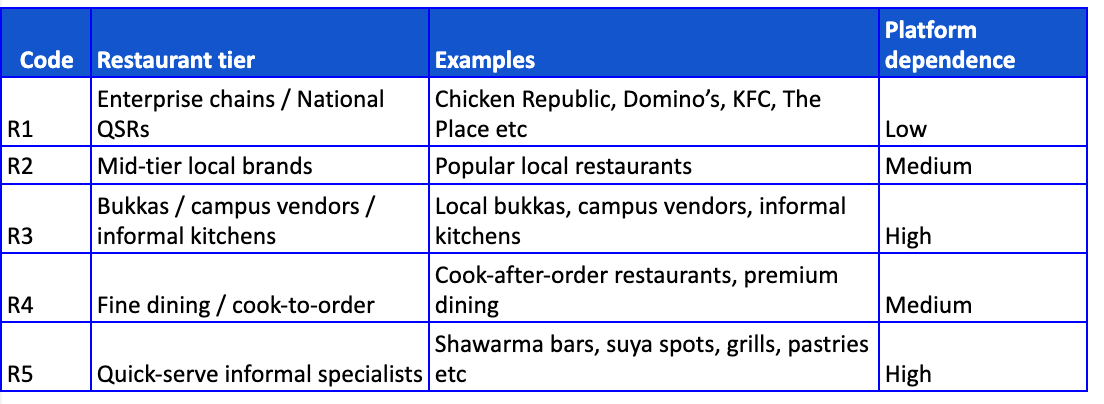

Lens 2: Restaurant tiers, the supply side is not equal

Supply is not one thing. Some restaurants need you. Some do not. Some will bend to your systems. Some will break them.

Table 2: Restaurant Type

Goliath starts where the supply is clean (R1). Nothing screams low platform dependence like the way Chicken Republic has terminated partnerships with these startups. David starts where supply is dependent on his platform (R3/R5).

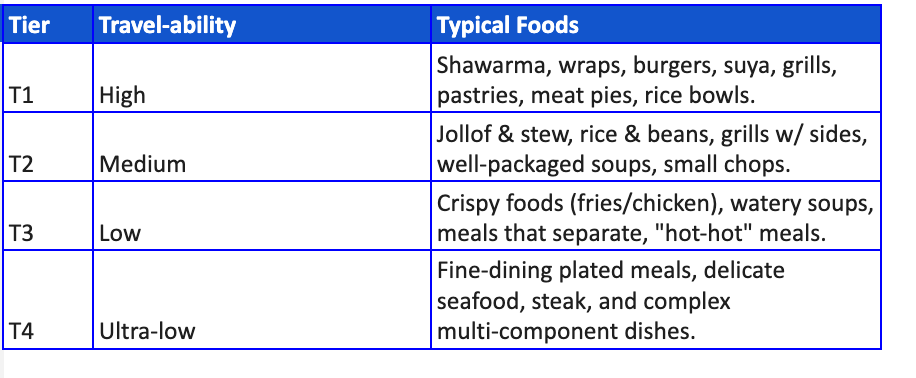

Lens 3: Food travelability, because food is not equally deliverable

Even with perfect dispatch, some meals degrade faster than others. Travelability is how food behaves under travel stress.

Table 3: Travel-ability of food. How well it keeps when delivered.

Scene 2: Goliath’s Playbook

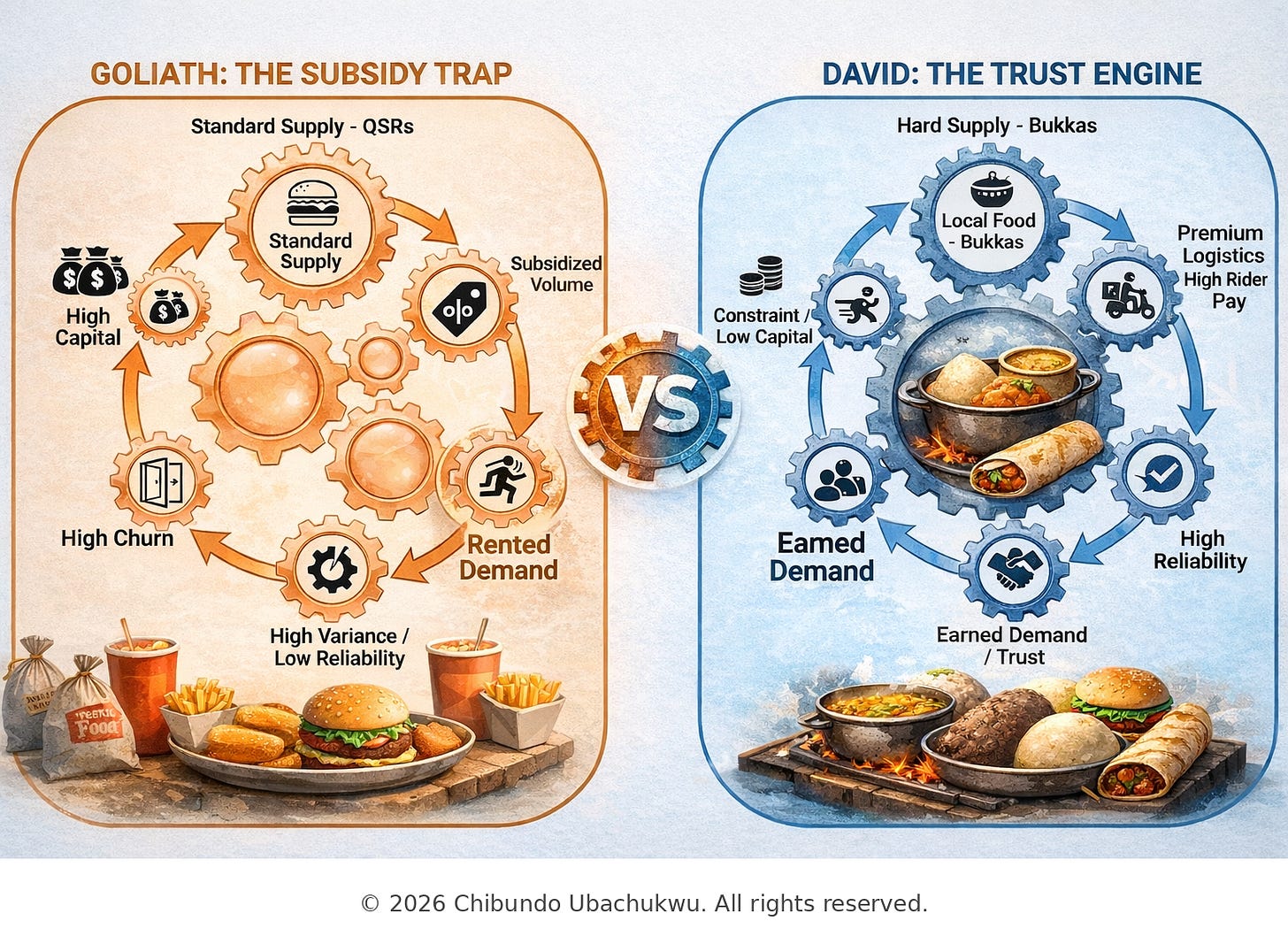

The giants came in rational. They came in with a supply-side playbook. Coverage. Brand anchors. Marketing spend. Subsidised volume. It is the instinct of a company that already has distribution muscle.

Jumia

If you are Jumia and you are early in the category, your first job is market education. So you start with the safest supply.

You anchor the catalogue with national QSRs and big brands that already have standard menus, brand names, packaging discipline, and predictable prep. You make the category legible. You tell people, order what you already trust, now delivered. And because you already have a marketplace with a broad consumer reach, you can blast the message at scale and manufacture early volume. That is rational.

Bolt Food

Bolt’s logic is also rational. Bolt already owns trips. It already owns urban movement. Food delivery becomes an adjacency, and the fastest wedge is premium density.

So you start where the order values are higher, where people can pay for convenience without negotiation, and where the restaurant supply is already concentrated. That is why Bolt Food’s initial Lagos rollout focused on Lagos Island corridors, Ikoyi, Victoria Island, and Lekki, with over 100 restaurants at launch, before expanding into the mainland.

Glovo

Glovo came in with a different hedge.

From day one, the company positioned itself as more than restaurant delivery. It leaned into quick commerce, not only meals. That matters because groceries and essentials create frequency, and can subsidise learning in food if needed. In Nigeria, their later Shoprite partnership is a clear signal of their posture.

Part B: David’s Playbook

Scene 3: Flank Attack

David does not have the money to subsidize three sides of the market. So he does the most rational thing.

He serves the type of customers that his seniors cannot serve. He partners with suppliers that are too local. He pays his bikers more than the competition to keep them. And he needs to make margins while doing this.

If David had the resources and size of Goliath, this strategy would look irrational. Under constraint, it becomes the only rational path.

They went to Yaba. Partnered up with local kitchens. The team would sometimes advance money for ingredients and help merchants organise supplies. Then they sold Eba and Amala, foods that do not travel well, but sit at the centre of how people actually eat.. Pizza is tiny by comparison.

This is non-consumption on four axes.

1. Suppliers (Supply-Side Non-Consumption). These were vendors that no one else could work with. They were outside the digital economy. You technically had to ‘invent’ them as digital suppliers before they could be valuable to you.

2. Food Types (Product Non-Consumption). I do not even buy takeaway Eba. I just buy soup and go home because Eba and soup travel so poorly. Nkwobi, Amala, and Ewedu - these are foods core to our culture, but they are ‘logistically difficult’. By delivering foods the giants avoided (Table 3, Tiers 3-4), Chowdeck built operational muscle where competition was weakest.”

3. Customers (Demand-Side Non-Consumption). The giants looked at the average income in Akoka and looked away. But the students were not unwilling to buy. They were just non-consumers of expensive, corporate fast food. By offering them local vendors, local portions, and a price point that made sense, Chowdeck did not steal customers from KFC. It created customers out of thin air.

4. Riders. Make riding attractive to folks who would never have driven a delivery bike.

From my rough calculations, Jumia Food made a loss of $2.2 per order in FY 2022. And $0.7 per order in FY2023. The giants rented customers. Chowdeck earned customers. Subsidized demand hides the truth about product-market fit.

Scene 4: Selling Trust

I have compared prices on my app. Glovo comes out cheaper almost every time. Cheaper food. Cheaper on logistics. Cheaper on Prime.

Chowdeck was the first to raise prices in 2023 when the petrol subsidy was removed in Nigeria. And they raised it by over 50%. Their CEO revealed that Chowdeck made a decision not to compete on price.

Why do people still choose the more expensive option? Why Chowdeck?

Because in Lagos, speed is not the product. Reliability is. And reliability is made of two things: low variance, and decent recovery when things break.

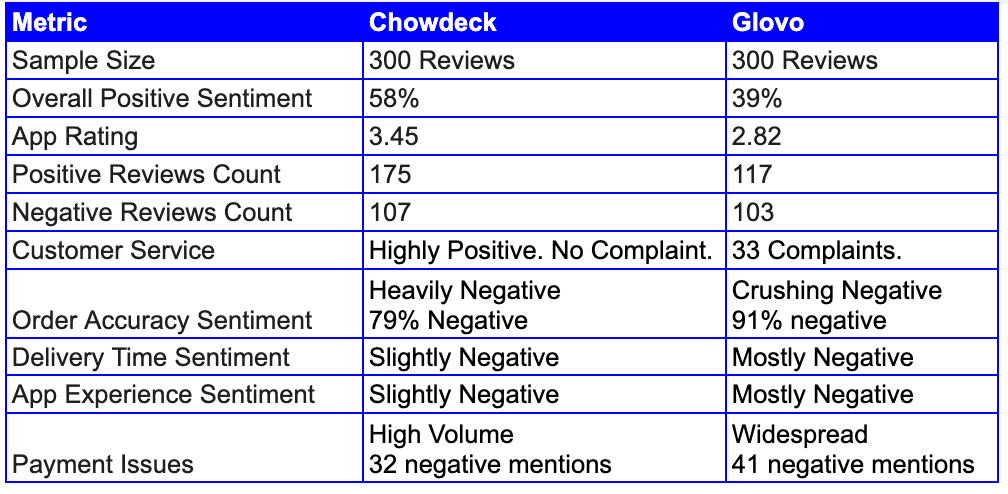

Sentiment is one proxy for that.

Anselem Kadiri’s review-based sentiment analysis (300 Google Play reviews each for Chowdeck and Glovo) shows Chowdeck ahead on overall satisfaction, but also shows the industry is suffering from the same trust killers: wrong orders, payment issues, delays, and weak support. (3)

Here is the clean comparative snapshot from his write-up.

Source: Kadiri, 2025.

Chowdeck still messes up, but support shows up, and that changes how failure feels.

And for Glovo? 33 complaints on customer service. Worse on every sentiment, including delivery.

Now the paradox.

TechCabal ran a real-world speed test ordering the same meals from the same restaurants at the same time, and Glovo beat Chowdeck in both the morning and evening tests. The same piece points to a key reason: order batching.

A spot test can show who is faster on a Tuesday. Customers do not live inside the average. They live inside the worst 10% of outcomes. Average delivery time is a weak signal. Tail failures define perception.

In a market where every platform is imperfect, the winner is not the one with zero failures. It’s the one whose failures don’t feel like abandonment.

So Chowdeck’s edge is not “fastest on average.” It is cheap enough, fast enough, things break less often, and when they break, “customer service” shows up.

That is what people pay for.

Scene 5. They did not act their age.

The ‘Dean of Valuation,’ Aswath Damodaran, argues that ‘More value is destroyed by companies not acting their age than by any other single factor.’ In emerging markets, this takes a specific form - the imported playbook.

When a global startup enters a new category or an untested country, it becomes early-stage again. The old brand travels. The old cap table travels. But the thing that matters does not travel, proven fit inside the new constraint system. New customers. New unit economics. New supply realities. New failure modes.

So the laws of the early stage apply again, whether we respect them or not.

That is the first mistake the giants make. They enter acting like late-stage companies because that is what they are back home or in their core category. But in this new market, they are still searching. And in search mode, burn is not an investment. If you spend too much, too early, you don’t buy learning, you buy illusion.

This is where Goliath becomes fragile. The giant’s biggest problem is path dependence. The initial investments then harden a flawed strategy into structure. Headcount. Partnerships. Vendor contracts. A sales org trained on the wrong promise. A product roadmap built for the wrong buyers.

Then reality shows up and invalidates the model. A pivot now costs reputation internally and cash externally. So the giant keeps going because stopping would force the truth.

David is different for one reason. He cannot afford illusion.

He starts small because he lacks the luxury of being wrong at scale. So he is forced to respect early-stage physics. He tests in tight loops. He stays close to the ground. He learns the terrain, the people, the edges, the true frictions.

And he targets what the giants ignore. Non-consumption. The people who are not consuming at all because existing solutions are too expensive, too unreliable, too slow, too complex, or simply not designed for them. But David still does not scale until he validates both demand and supply. Only after both loops hold does scaling make sense. Before that, scaling is just multiplying an error.

And this is the dangerous part. David’s advantage is not eternal. It is conditional. If Chowdeck scales by spreading coverage too early, batching too aggressively, underpaying riders, or expanding into new categories before the loop holds, it will recreate the same tail failures it once exploited.

Acting your age is not a one-time strategy. It is a discipline you must keep renewing. The real test is whether David can grow up without becoming the next Goliath.

I am here to remind us so we do not forget.

References

Christensen, C. M., Ojomo, E., & Dillon, K. (2019). The prosperity paradox: How innovation can lift nations out of poverty. Harper Business.

Chukwu, N. (2025, 2 June). What is Lagos’ fastest food delivery app? I tested Chowdeck, Glovo, and FoodCourt to find out. TechCabal. https://techcabal.com/2025/06/02/the-fastest-food-delivery-app-in-lagos/

Kadiri, A. (n.d.). Nigeria food delivery apps: Sentiment analysis of Glovo, Chowdeck & FoodCourt. Medium. Accessed 28 January 2026. https://medium.com/@anselemkadiri/nigeria-food-delivery-apps-sentiment-analysis-of-glovo-chowdeck-foodcourt-9911ab68af3b

Oladunmade, M. (2023, 3 November). How YC-backed Chowdeck hit ₦1 billion in monthly order value. TechCabal. Accessed 28 January 2026. https://techcabal.com/2023/11/03/chowdeck-1billion/