How did Elon build the most technical startups in the world and fail at a government job?

Most of what we call systems thinking in business is quietly built on a mechanistic view of systems.

It assumes the system is a machine with compliant parts. Find the bottleneck, elevate it, subordinate everything else, repeat. That logic works beautifully when the system is mostly physical flow, stable constraints, and low politics. So it gets you results in a factory line or a call center. This is why the Theory of Constraints is such an effective model in those regimes.

Now go use TOC in a government agency. Goodluck.

You see across scientific fields, we recognize that systems differ fundamentally. And each kind of system requires different kinds of laws.

Physics, non-purposeful systems. Physics studies objects with no will and no preference. Planets do not negotiate gravity. Causality is stable. If you repeat an experiment a thousand times, you expect the same outcome.

Chemistry, constrained interaction systems. Chemistry studies substances that interact in predictable patterns but with more complexity than physics. But still, no intention. A reaction either has the required activation energy or it does not. Chemistry is a world of reliable rules, only more conditional.

Biology, adaptive purposeful systems. Biology breaks the pattern. Biological systems respond rather than behave. They adapt. They compensate. They pursue survival. And they respond to their environment. And this means the laws become probabilistic. You predict tendencies, not certainties.

Social sciences, fully purposeful systems. And then you reach social systems. Clubs, markets, governments, and businesses made up entirely of purposeful agents. Individuals with goals. Teams with incentives. Managers with fears. Leaders with biases.

Here, nothing behaves. Everything responds. Causality becomes conditional. Effects depend on context, interpretation, history, power, trust, and incentives. Physics gives you universal laws. Social science gives you moving targets. The laws of one domain do not translate cleanly to another. What holds true in a mechanistic system often fails to apply in a social system.

I have a friend who’s an engineer, and he tried to explain everything through that lens. When conflict showed up, he’d reach for Newton. Every action triggers an equal and opposite reaction. Not a bad instinct, honestly, just incomplete.

When people weren’t performing, he called it inertia. “They won’t move unless you push them.” And when a process was slow, he blamed friction and went looking for ways to lubricate it.

But the more he pushed and lubricated, the more the system changed shape. People didn’t just “move.” They interpreted. They resisted. They complied on the surface and defected underneath. They protected status. They conserved energy. They negotiated meaning.

He wasn’t dealing with particles. He was dealing with purposeful agents. He was importing laws from one domain and demanding they behave like universals in another.

That’s why someone can send rockets into orbit with breathtaking reliability, yet struggle to reform a ministry. A rocket is obedient. A bureaucracy is not.

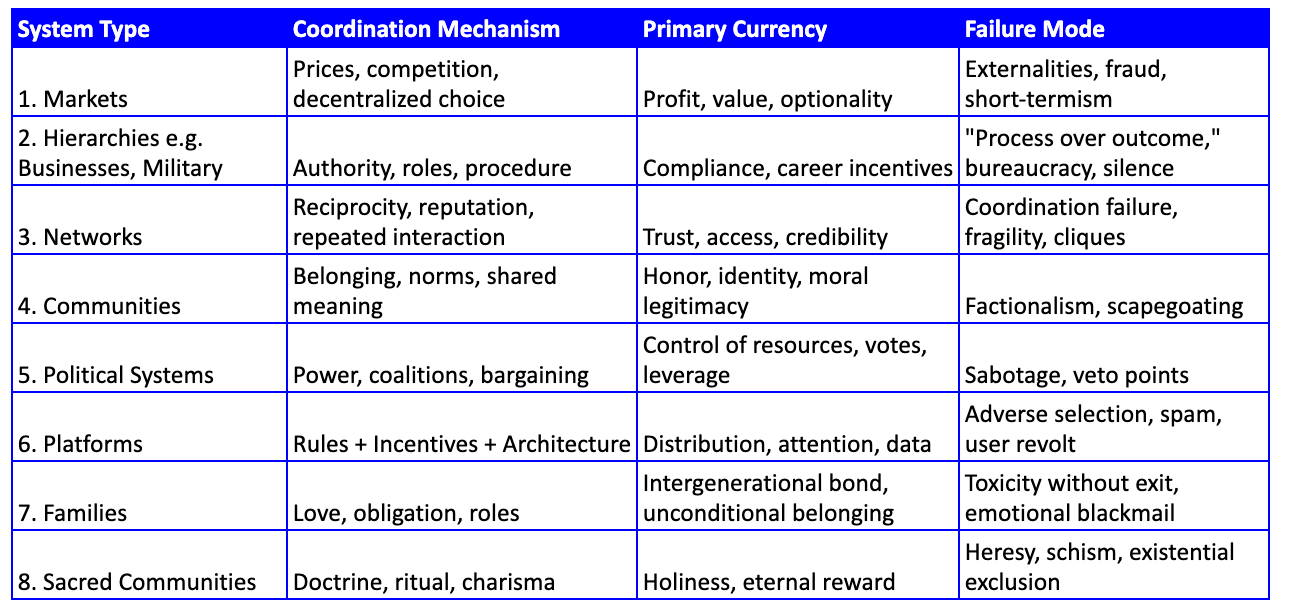

And even within social systems, the rules differ. Markets, bureaucracies, political arenas, and firms do not run on the same mechanics. There are at least 8 kinds of social systems.

First-principles thinking wins where constraints are physical. It struggles where constraints are political.

Most business leaders make the same mistake as Elon. They apply the logic of mechanistic systems to social systems. They assume that if they pull a clean lever, business outputs will change proportionally. If they add pressure, performance will rise automatically. If they tighten the rules, behavior will stabilize.

But organizations do not behave like machines. They are made up of people. And every person is a purposeful part, responding, interpreting, protecting, and optimizing for their survival. A rocket responds to equations. A company responds to incentives, fear, power, identity, meaning, history, and interpretation. That is the nature of the systems we lead. Even under extreme coercion, human beings retain agency.

Once you understand that organizations are social systems, your approach to systems thinking will change.

Work is not the task on paper. Work is the translation from strategic intent to action through purposeful agents. It passes through interpretation, incentives, capacity, coordination, local tradeoffs, competing priorities, fear and ambition, negotiation and conflict.

This phenomenon is why outcomes often surprise leaders. They erroneously assume that they are managing a well-oiled machine. But in reality, they are leading a network of purposeful translators who would optimize for themselves when incentives are not aligned.

Once, a leader called me crying, “Our best salesman just quit.” So I empathized with him first. And then I picked up my notes.

Ontology. The system changed. Team composition and structure shifted overnight.

Dynamics. Execution capacity took a hit.

Ecology. The talent market and competing offers enabled the exit.

Teleology. The exit revealed meaning. When your best people leave, it is rarely only money. It is often misalignment on value, growth, fairness, or what the work is for.

He did not find it funny, but we must learn systems thinking.

In social systems, events are not incidents. They are signals. And if we refuse to read them as system feedback, we will keep treating symptoms and calling it management.